Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada is Associate Professor of Religion at Kalamazoo College where she teaches classes on religion and masculinity, Catholics in the Americas, urban religion, and religions of Latin America. She is an ethnographer and her research focuses on material culture, contemporary Catholicism, and gender and embodiment. She is the author of Lifeblood of the Parish: Men and Catholic Devotion in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, an ethnography about masculinity and men’s devotional lives in a gentrified neighborhood in New York City. She is currently working on her second book project: Reinventing the Rosary: Innovation and Catholic Prayer. She is editor of the journal Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief, co-chair of the Men and Masculinities Unit at the American Academy of Religion, and serves on the editorial board of the journal American Religion. She was chosen as one of the Young Scholars in American Religion at IUPUI’s Center for the Study of Religion & American Culture. She received her Ph.D. in Religion from Princeton University and her B.A. in Sociology and Religion from Vassar College. Follow her on twitter @emoprofessor

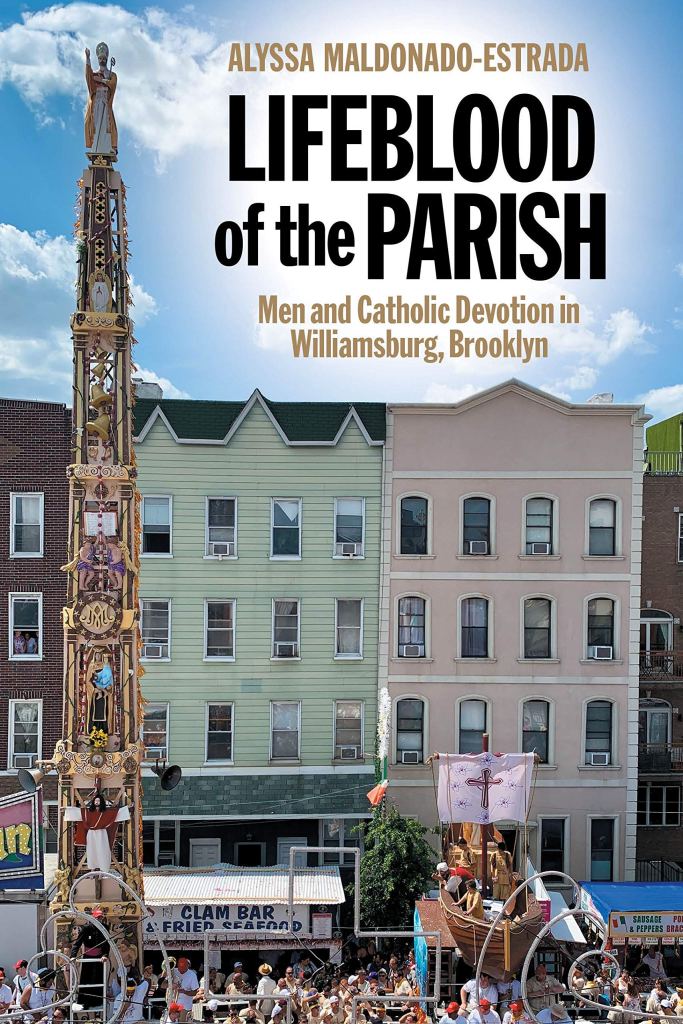

Lifeblood of the Parish: Men and Catholic Devotion in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

NYU Press | 2020

A New York City ethnography that explores men’s unique approaches to Catholic devotion

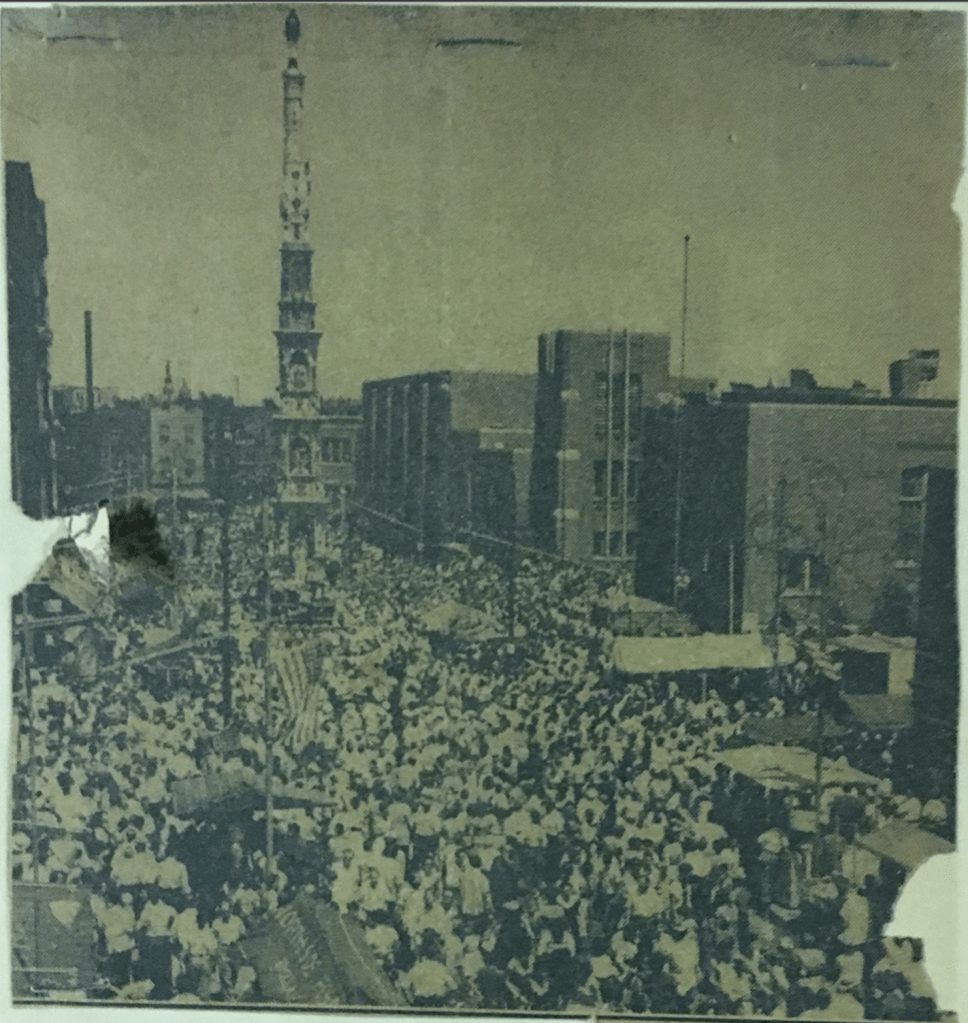

Every Saturday, and sometimes on weekday evenings, a group of men in old clothes can be found in the basement of the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Each year the parish hosts the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and San Paolino di Nola. Its crowning event is the Dance of the Giglio, where the men lift a seventy-foot tall, four-ton tower through the streets, bearing its weight on their shoulders.

Drawing on six years of research, Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada reveals the making of this Italian American tower, as the men work year-round to prepare for the Feast. She argues that by paying attention to this behind-the-scenes activity, largely overlooked devotional practices shed new light on how men embody and enact their religiosity in sometimes unexpected ways.

Lifeblood of the Parish evocatively and accessibly presents the sensory and material world of Catholicism in Brooklyn, where religion is raucous and playful. Maldonado-Estrada here offers a new lens through which to understand men’s religious practice, showing how men and boys become socialized into their tradition and express devotion through unexpected acts like painting, woodworking, fundraising, and sporting tattoos. These practices, though not usually considered religious, are central to the ways the men she studied embodied their Catholic identity and formed bonds to the church.

Media

Fashioning Masculinities Post-Bad Bunny: World-Building & Aesthetic Play in Contemporary Reggaetón: A Presentation at the Thinking With Bad Bunny Symposium at CENTRO: Center for Puerto Rican Studies

How can we understand contemporary reggaeton icons through an exploration of their style? What does reggaeton look like post-Bad Bunny? This presentation explores fashion, regional imaginations, and the shifting terrain of reggaeton masculinities.

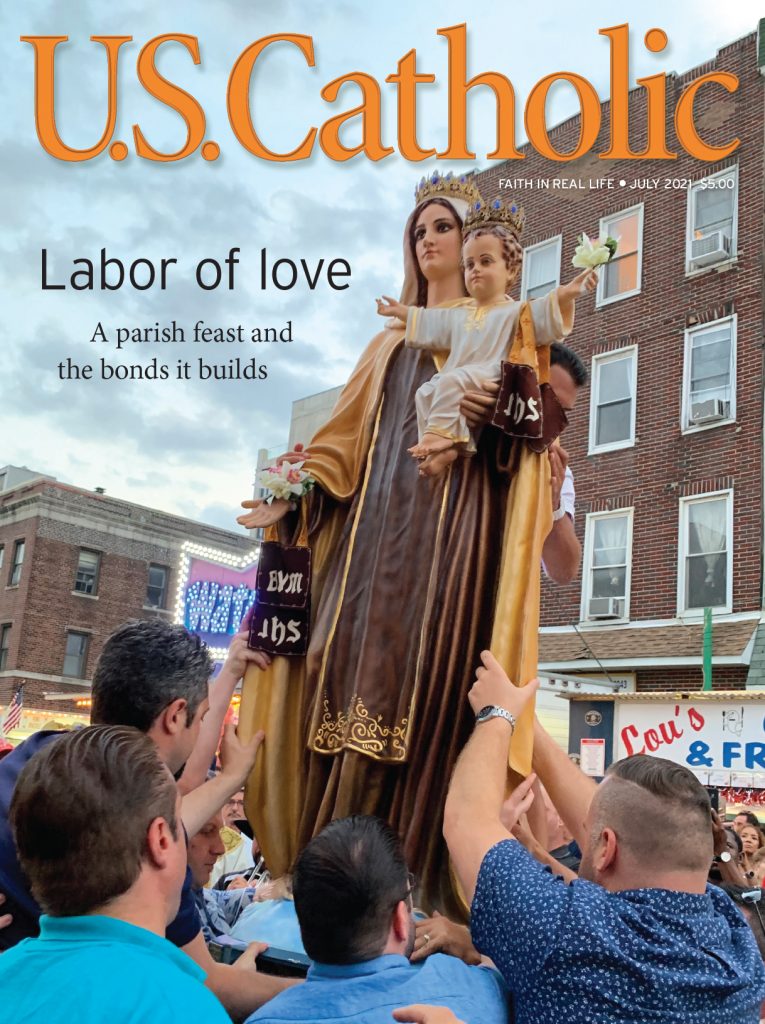

(Interview with U.S. Catholic Magazine) The men involved in the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel find God not only in Mass and prayer, but also through manual labor, tattoos, and family ties.

“Masculinity and the Body Languages of Catholicism” | The Religious Studies Project Podcast

From counting money to lifting four-ton statues, Italian Catholics in Brooklyn have a robust, embodied language to express their masculine devotion says Prof. Maldonado-Estrada in this interview about her new book, Lifeblood of the Parish.

Lifeblood of the Parish | Empire State Engagements

Dr. Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada spoke about her ethnographic study of Italian-American men’s Catholic devotion in Williamsburg, Brooklyn: Lifeblood of the Parish (New York: NYU Press, 2020). We discussed her experiences over six years of work engaging the parish community; reading tattoos as devotional texts; playfulness and devotion in masculine spaces; the rich history of Italian-American Catholicism in Williamsburg; the dynamic career and peculiar death of the pioneering Father Peter Saponara; the financial realities of community devotion; and the endurance of this parish, tradition, and community–despite decades of challenges ranging from reactionary clergymen to Robert Moses to gentrifying hipsters.

“Studying Masculinities, Catholic-Style” | American Catholic Historical Association

How does Catholicism intersect with and shape notions of masculinity? What historical and ethnographic sources are available for answering such questions? Our panel debated these issues at the first of our 2021 Winter Webinar Series.

The Classical Ideas Podcast: EP 173 with Greg Soden

I discuss Lifeblood of the Parish, growing up in New York City, and the many surprises that come with doing ethnography.

The Instagram witches of Brooklyn | BBC World Service

Featured expert in the BBC’s first Instagram documentary, from filmmaker and religion reporter Sophia Smith Galer.

Writing

Material Catholic Afterlives: Archaeological Notes on Sacrality and Secondhand Shopping | U.S. Catholic Historian

This article is an ethnographic archaeology of Catholic material culture as it circulates through secondhand economies. Via estate sales, auctions, antique shops, flea markets, thrift stores, eBay, Instagram, and Etsy, Catholiciana is bought, sold, and recontextualized for new ownership every day. In the contemporary U.S., several structural patterns—parish closures, the decline in Catholic adherence, and the death of a generation of Catholics who maintained extensive personal devotional collections—intersect to create conditions in which Catholic materials become secondhand commodities.

We explore how circulation is structured by the technological affordances of devotional material; how the sensory and social histories of objects are erased through patterns of discard and partially recovered through traces of use; and, how discovered objects are presented to market publics by actors with divergent stances toward institutional Catholicism. Ultimately, we attend to Catholic objects as both devotional and disposable in order to better understand how objects pass in and out of the commodity state, their shifting valuation, their appeal to different audiences, and recalibrations of power and potency.

Touching Lourdes: Collection & Tactile Pedagogy | Collecting Religion

In this piece on collecting objects from the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes, I reflect on touch as research method and the possibilities of using religious objects in the classroom. Rosaries, canteens, postcards, lozenges, and bottles of miraculous water—my treasures are pretty mundane. And yet they are also part of the history and circulation of the miraculous. I grow my collection to develop a tactile pedagogy and allow students to explore “touch as a way of knowing.” The Lourdes teaching-collection allows students to engage their whole sensorium as a way of learning about religious history.

The Awkward Engagements of Material Religion & The Stuff of Material Religion | Material Religion

In this duo of manifestos, I dream of replacing the words “object” and “belief” in Material Religion: the Journal of Objects, Art and Belief with “stuff” and “sensation.” A stuff approach to material religion would orient us more fully to the making of objects and things and spaces and bodies, and allow us to explore all of the weird, magical, mundane, trajectories and sensory affordances of things used by and for religious practices.

Latinx Devotional Stuff and Material Religion | Bloomsbury Religion in North America

To study the materiality of religion is to explore all of the stuff, sensations, and substances of religious life. To study material culture is to explore how aural, olfactory, tactile, visual, and gustatory sensations are essential to religious ways of knowing. Being part of a religious community is often about cultivating a certain sensorium, and becoming attuned to certain sights, sounds, and tastes, and to be in touch, literally and figuratively, with sacred spaces, gods, spirits, ancestors, and the dead.

I explore Latinx material culture in New York’s Lower East Side, San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and Chimayó, New Mexico and argue that Latinx devotional stuff is eclectic and pragmatic, built on relationships of reciprocity, and creative in its use of mundane materials. The aesthetics and assemblages of Latinx material culture often refuse and contradict neat distinctions between religious traditions and “spiritual commodities.” In Latinx religious material culture we find people pursuing wellness, healing, and protection from objects and substances beyond the bounds of traditional religious orthodoxy.

Rosary Revelations: The History of Prayer | University of Dayton, Marian Library

This past summer, I was fortunate to receive the inaugural Visiting Scholar Fellowship at the Marian Library to support my research for the book. The Marian Library is full of treasures — my favorite kind of treasures: the material culture of Catholic devotion. In its collection, I pored through boxes of carefully cataloged rosaries. There were electronic rosaries; rosaries designed especially for steering wheels and gear shifts; and rosaries made from surprising materials — such as peach pits and horse hair. As a scholar of material culture and embodiment, handling these objects was important. Feeling the size, temperature, texture and even smell (some scents were pleasant, others were rancid!) of the beads is essential for understanding the sensory dimensions of prayer.

What should Catholics think of tattoos? | U.S. Catholic Magazine

A search of #catholictattoo on Instagram yields thousands of results. Our Lady of Sorrows cries juicy tears on biceps. Rosaries snake down forearms and wrists; sacred hearts in full color burn on chests; and Virgin Marys stomp snakes from reddened, puffy freshly inked skin. #religioustattoos yields tens of thousands more images, many of them Catholic. Catholic imagery seems increasingly mobile and personalized, made newly portable by being inked into the skin.

For centuries, Catholics have rendered their religious journeys, their devotions, and their communal identities permanent in flesh. Today’s burgeoning tattoo culture reflects the history of Catholic votives, sacramentals, and pilgrimages and the many physical ways Catholics have entered into relationships with sacred places, the saints, and one another.

Sacred Spaces: Special Mosque Edition | Dig Boston

Though more and more American Muslims are worshiping in newly constructed mosques, most mosques and prayer rooms were not and are not in purpose-built spaces. While desacralized churches are being retrofitted to serve as luxury condos, Muslims have for decades been engaging in the opposite task—finding ways to make residential and commercial buildings fit the very particular mold of a Muslim worship space.

Sacred space is ritual space, and as Muslim communities adapt and repurpose buildings they create spaces hospitable to and appropriate for prayer. Ritual and embodied practices do the work of consecrating spaces—“through the spoken word, prayer, and the remembrance of sacred events, space is made Muslim…” So it is the combination of creative adaptation through the addition of interior elements, and the consistent use of these spaces for salat and community gatherings that allow for the creation of Muslim space in buildings that were formally homes or offices.

What would it illuminate to tell the story of Latinx Christianity through the life of one woman? Carmenza is a fifty-five-year-old Colombian immigrant and US citizen living in Queens, New York. She grew up in Medellín but moved to New York City when she was nineteen. Catholic devotional traditions were an essential part of her upbringing in Colombia, and when she became a mother, she attempted to introduce her children to Colombian Catholic traditions. Her neighborhood—a multiethnic, densely diverse community in Queens—offered many churches she could attend. Carmenza moved between Catholic, mainline Protestant, and evangelical churches. Hers was not a straightforward story of “defection” from Catholicism; it had starts and stops. She eventually defined Christianity for herself and cultivated a personal relationship with God outside of any one denomination. Carmenza’s story challenges histories and ethnographies of Latinx Christians, offering a lived, textured view of how gender, neighborhood, and national identity challenge a neat, monolithic idea of Latinx Christianity writ large.

My Poison Rosary: On eBay and Desire | Material Religion

I have a poison rosary. My precious, hazardous sacramental is in a closet, inside a plastic bin, inside a little cardboard box, and wrapped in bubble wrap. Exploring the process by which I discovered and purchased this rosary opens up a conversation about user experience, the compelling and toxic substances that devotional objects are made out of, and the webs of sensation, value, and desire that we as scholars create and find ourselves in as we pursue knowledge about and ownership of other people’s devotional stuff.

City churches were designed to be walkable and serve their immediate neighborhoods, but as historically working-class or African American neighborhoods gentrify and longtime residents move away, commuting by car rather than walking to church becomes far more common for those keeping ties to their religious communities. This is the case for the South End’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, a congregation that was founded by formerly enslaved people and Southern migrants.

Church closures and desacralizations are increasingly common in American cities, and many large, historic churches in Boston have become exemplars of this trend. Historically African American congregations have been particularly vulnerable to the societal and financial pressures that force the closure and sale of church buildings in major cities—population shifts, mounting maintenance costs, and rising real estate prices.

Hannah Medeiros (@sadgirl_tattoos) and Pauly Lingerfelt (@paulylingerfelt) are tattoo artists known for their work with Catholic imagery and iconography. They not only tattoo saints and Sacred Hearts, but also surround themselves with devotional stuff in their studios and homes in Rhode Island (Hannah) and New Orleans (Pauly). I spent time with these two artists, getting tattooed, geeking out over our love of Catholic objects, our obsession with collecting, and thinking about the role their own religious histories played in their art. Through these conversations we explored the devotional aesthetics of their tattoos and spaces, their sentimental and enchanted objects, and how their collecting shapes their art.

Gentrification might seem to be a secular or secularizing force, hastening parish closures and mergers, and dissolving or displacing aging ethnic communities… Gentrification becomes part of sacred narratives communities tell about themselves, fitting into collective memory. Religious communities re-signify rituals as acts of resistance to broader demographic changes and municipal policies. More, urban development shapes the meaning of devotion. Within discussions of urbanism we need to think less about religion as synonymous with church buildings and what happens behind those walls. Instead, we should explore how religious communities dialogue with development and gentrification.

Men, Tattoos, and Catholic Devotion in Brooklyn | Material Religion

This article explores the religious lives of Catholic men in Brooklyn, particularly focusing on their tattoos of saints and Catholic objects. It argues that tattoos are much like devotional objects: they are votive and function like sacramentals. Like scapulars, medals, and rosaries, tattoos can be efficacious conduits for protection and materialize love of the saints and Virgin Mary. More, tattoos illuminate the devotional lives of lay men. Every July in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Italian-Americans celebrate the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and Saint Paulinus, the patron saint of Nola, Italy. The central event of the feast is the Dance of the Giglio, a spectacular devotional ritual in which over one hundred men lift a seventy-foot-tall, four-ton devotional tower. In exploring tattoos of the giglio and other saints, this article argues that men’s devotion is relational—the saints are always inflected with their connections to mentors, fathers, friends, and kin. They enact devotion together through shared bodily labor. Tattoos materialize the very real and affectionate intergenerational bonds men form with each other in church and in religious ritual.

Catholic Devotion in the Americas | Religion Compass

This article surveys scholarly contributions to the study of Catholic devotional practice in the Americas, tracing how historical, sociological, and ethnographic studies have examined the relationship between devotion, gender, and embodiment. Scholars have explored how the saints have been brought to bear on the conditions of daily life including immigration and migration, suffering, and social change. Women’s devotion has been at the center of studies of gender and lived religion, as scholars explore the creative and tensile ways, women’s religious practice has exceeded the institutional authority and architectural boundaries of the church. This essay ends with a provocation about how the study of men and masculinities can challenge the portrayal of devotion as an exclusively feminine domain and complicate the binary of (male) clerical authorities/women that pervades studies of religious practice and materiality.

Loving Saint Paulinus: Patron Saint of Brooklyn | The Global Catholic Review

Nola, a small town outside of Naples in the Campania region of Southern Italy, and Williamsburg, the premiere trendiest neighborhood in New York, are approximately 4,394 miles apart. Nola with its stone streets and ancient grit, is in the shadow of Vesuvius, while Williamsburg is ultra-gentrified and punctuated by high-rise glass condominiums and the shells of old Brooklyn factories. Still, both are central to Italian-American Catholic practice in Brooklyn. What these places share is intense love for Saint Paulinus (~353-431 AD), more affectionately and colloquially known as San Paolino, the patron saint of Nola. Although Italian-American men in Brooklyn might be separated from Italy by generations, what they share with those in Nola is a feeling of devotion in their bodies and in their bones. To love San Paolino is to reenact his hagiography each year, through costuming, ritual and devotional play. While public discussion about the feast in his honor centers on a dying or threatened tradition, there is a larger story here about an enduring devotion among men.

Tattoos as Sacramentals | American Religion

Summer in Brooklyn means exposed limbs, especially at the annual Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Williamsburg. One man’s story reveals how tattoos are devotional media. Joe’s body is covered in tattoos, most of them “cultural or religious” according to him.

Like any devotional object, a tattoo can range from artful to pedestrian. Despite the skill, virtue, or intent of the creator, its use, display, and personal and communal meaning matter much more. Tattoos are key sources for the study of religion. They are much more than visual markers of individual belief or values, “texts” writ on the body, or repositories for stories of the self. By this I mean they are more like objects: they are in use, activated, and even efficacious. Tattoos are not just signs of devotion. Wearing them constitutes an act of devotion, much like using a sacramental or making a votive offering.

Teaching

Here I share how I used Instagram as a replacement for slideshows and more traditional Moodle posts, allowing students to engage aesthetically and analytically with course materials in ways that felt personal and accessible.

Courses Taught at Kalamazoo College

Bad Religion

Ethnography of Religion

Media, Technology, and the Supernatural

Devotional Stuff

Urban Religion

Catholics in the Americas

Religions of Latin America

Religion and Masculinity in the U.S.

Junior Seminar in Religion—Theory and Methods

Editorial

Editor

Material Religion is an international, peer-reviewed journal which seeks to explore how religion happens in material culture – images, devotional and liturgical objects, architecture and sacred space, works of arts and mass-produced artifacts. No less important than these material forms are the many different practices that put them to work. Ritual, communication, ceremony, instruction, meditation, propaganda, pilgrimage, display, magic, liturgy and interpretation constitute many of the practices whereby religious material culture constructs the worlds of belief. Highly visual in terms of content and in color throughout, this refereed journal bridges the world of scholarship and museum practice, and supports all those seeking, at whatever level, to understand and explain the relationships between objects, art and belief.

Sources Curator

American Religion: Sources as Provocations

Have a source you’d like to spotlight? Email me!

How might we make American religion more capacious? What sources—ethnographic, material, sensory, and historical—can provoke new narratives, stories, and documentation of religion in the Americas? What are the procedures and rituals of accessing and analyzing those sources? How is finding, reading, and creatively or affectively engaging with sources part of the research process?

In this space we spotlight sources and provocations that enrich and challenge how and where we find, narrate, and study religious lives, spaces, imaginaries, and communities. We feature emerging field sites, findings from new or ignored archives, archives that give a global or hemispheric shape to American religion, object histories, and reflections on the sensory, bodily, visual, and material religion.